Uncovering pests in Te Aitanga Pepeke

What insights can whakataukī offer us into the nature of insect pests and pest control in Aotearoa? A team of Māori academics delved into te ao Māori with “pestiness” on their minds.

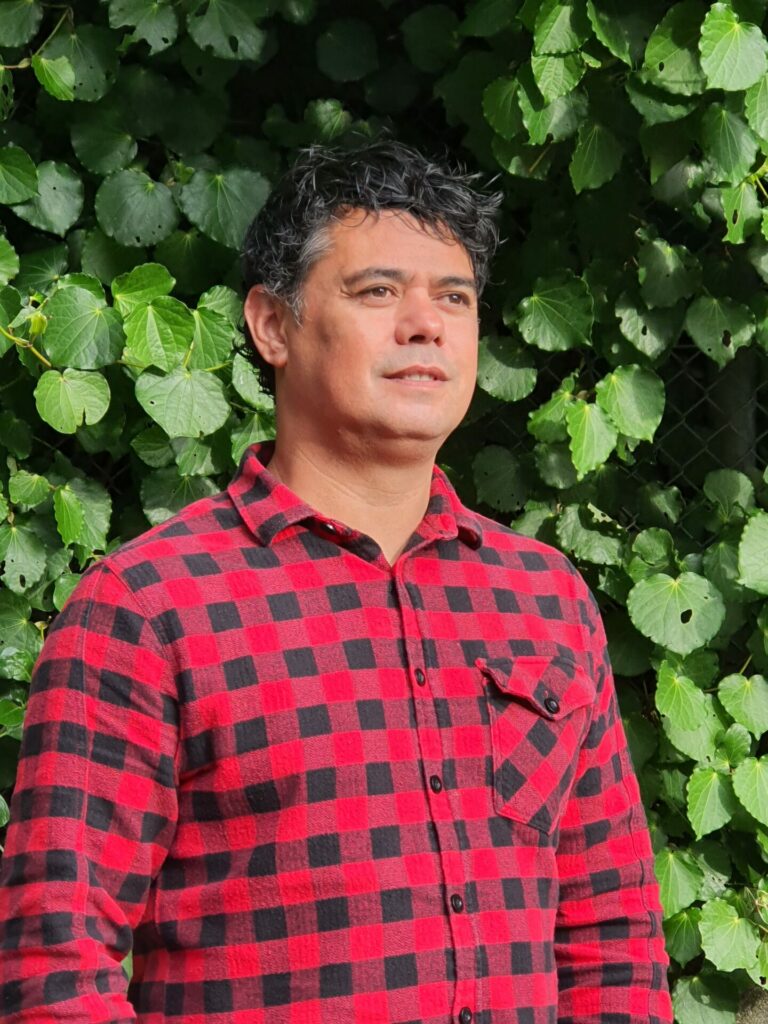

BioHeritage writer Kerry Donovan Brown spoke to Hōhā Riha: Pest Insect Control in Māori Tradition co-author Alan King-Hunt, discussing some of the team’s discoveries, including a surprising defender of historic kūmara plantations . . .

In Aotearoa, it’s difficult to go a day without crossing paths with an invasive pest invertebrate – with some of the more well-known culprits being the commonplace white cabbage butterfly, to more threatening species, like Argentine ants, the German wasp, and devastating Varroa mites.

Alan King-Hunt (Ngāti Hauā, Ngāi Te Rangi) sees understanding these multilegged (sometimes no-legged) critters as vital in restoring the health of native ecosystems, and believes Māori knowledge can broaden perspectives, and aid in making important decisions about pest control.

Alan, and his co-authors Ocean Mercier (Ngāti Porou) and Symon Palmer (Ngāi Te Rangi), looked at “early ethnographic texts” – including whakataukī (ancestral sayings), pūrākau (traditional stories), and karakia (incantations) – to explore how insects were viewed by Māori, particularly in instances in which they were seen as damaging.

“What we wanted to look at was whether there was any precedence for pests and pest control in ancestral Māori time.”

The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of a pest reads as “any animal, esp. an insect, that attacks or infests crops, livestock, stored goods, etc”. If there were species of insects Māori considered pests, what were the terminologies?

“When we looked at contemporary Māori dictionaries we came across words straight away,” says Alan. “One of them was riha (also a noun for head louse), another one was kīrearea. There was even kupu Māori for pest control. However, when we turned to resources from further back in time – resources that recorded whakataukī, pūrākau, whakapapa – there was very little evidence that these words were used in early times.” This suggests that ‘hōhā riha’ (nuisance pests) were experienced and managed differently from today.

Whakapapa (genealogy) charts Māori ancestry to atua (cosmological ancestors), as well as describing atua connections to the natural world, including Te Aitanga Pepeke, the world of insects (and similar invertebrates, like arachnids). Māori oral traditions record and convey these histories through time, so they’re a source of knowledge in how Māori have related to the natural world throughout the ages.

“When we went through repositories, we could see that early Māori were definitely preoccupied with what insects were up to,” says Alan. “However, we could not find a pest that was considered all bad, all of the time.”

A good example of an insect considered both friend and pest is the moeone/hāpuku, an endemic tiger beetle which is noted for both preying on potential crop pests and bothering crops itself. Other Te Aitanga Pepeke species that featured in the records include parasitoid wasps, tāwhanawhana (looper moths), namu (sandflies) and āwheto, caterpillars that munched through kūmara plantations (some of these kūmara connoisseurs probably arriving in Aotearoa from Hawaiki, hitching rides on plants carried in waka).

Some whakataukī link annoying human behaviour to Te Aitanga Pepeke, yet admiration for certain characteristics (for example, tenacity and persistence) also feature prominently.

— co-author Symon Palmer reads a favourite whakataukī during Te Wiki o te Reo Māori 2022

The team’s investigation shines light on management strategies (prominently in kūmara fields), including “extraction by hand, poisons, use of karakia ‘incantations’, fire and even biocontrol.” An early account of biocontrol has tamed karoro (black-backed gulls) released into kūmara fields to fill their stomachs with those hungry, hungry āwheto.

“Considering the objectives of Predator Free 2050,” says Alan, “we can go back in history, before the arrival of Europeans, and see that Tangata Whenua had a deep knowledge of what was going on in their ecosystems. It’s in whakataukī, it’s in waiata, it’s in karakia, that we can begin to get a glimpse of what early Māori thought about the occurrences of pests, and potential environmental solutions.”

This study was published as part of the Novel Tools & Strategies – Invertebrates research programme. To read this paper in full contact the authors directly or follow this link.

Kerry Donovan Brown

March 2023